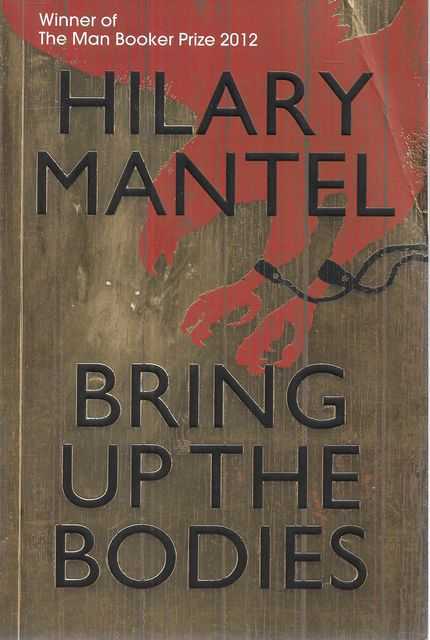

Far from easily charming, Mark Rylance’s Cromwell is a dour, taciturn figure, of few words and fewer smiles. According to episode one, Cromwell’s London was a drab, homespun place, and its residents equally understated in dress and demeanour. Sadly, no one seems to have given Peter Kosminsky, the director of the keenly anticipated BBC adaptation of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, the memo on this. Henry is one of the only characters permitted to wear colour. He was ingenious, keen to please, irreverently funny his energy seemed inexhaustible.

His contemporaries saw easy charm and social adroitness. The scowling asocial Cromwell is an invention of posterity, over-influenced by Holbein’s dour portrait. Writing in the Guardian, she reminds us that Thomas Cromwell was part of this world too: Hilary Mantel catches a lot of this passion and swagger in Wolf Hall. Satirists condemned the aristocracy and burghers for wearing too much bling: flaunting their status in chains of gold so heavy you were amazed they could walk at all. Foreign ambassadors were surprised by Englishmen’s capacity to weep openly and publicly at the slightest provocation. Equally, to imagine the interiors of English churches in the 1520s, think Andalusian gaudy rather than Hawksmoor’s classicist austerity, the walls covered in brightly painted scenes, the chapels filled with statuary and icons.Įarly Tudor London was a bright, brash and bustling place, unlike its whitewashed Protestant successor, and its inhabitants behaved in similarly extravagant fashion. Cheapside would have been a bustling surge of traders and customers, alive with noise and smells, packed with barrels and panniers of fish, fruit and spices, more like a bazaar than the modern city. In his biography of Sir Thomas More, Peter Ackroyd audaciously asks us to imagine pre-Reformation London as the street markets of Marrakesh.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)